|

Magnetic Losses |

|

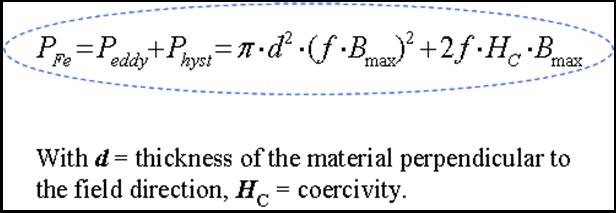

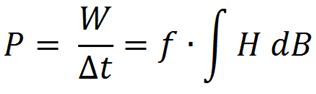

A general form for the magnetic + electrical losses (for a magnetic and conductive material such as Fe (iron) is: |

|

Different magnetic materials, though, display very different magnetic behaviors regarding magnetic losses. For the most common types of magnetic order found in solid state, the hysteresis loops are shown in the figure below. |

|

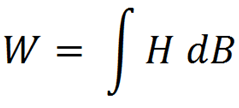

The idea of studying magnetic losses is to understand how are the several mechanisms involved affecting the whole power dissipation. The amount of energy involved in each cycle (see left figure) is just the area of the M(H) curve. So it is clear that if you want to control the amount of this dissipated energy, you must design a material with the adequate MxH response. From general arguments we can determine some of the parameters governing the dissipation of energy. For example: Resistivity/conductivity: Form metallic materials, the conductivity s will influence the facility to generate eddy currents on the material's surface. Magnetic hardness: The (maximum) magnetic field strength H for the magnetic losses will determine the final amount of energy dissipated. This is true up to the saturation value, above which all the magnetic moments are already aligned with the field, so there is no more changes in the magnetic structure of the material. |

|

All the above irreversible mechanisms sum up to dissipate energy, taken from the magnetic work done by the external field. |

|

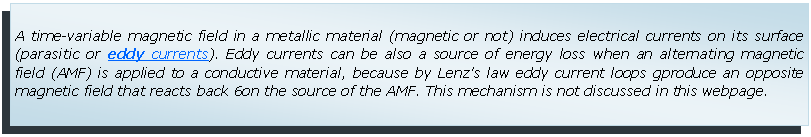

The term magnetic losses applies to the energy dissipation taking place in a material when exposed to an alternate magnetic field. However, depending on the properties of the material, there can be two (quite different) ways by which the energy dissipation can take place: 1. Eddy current losses refers to the energy dissipated by free electrical charges (typically the electrons in a metallic material). These charges are set in movement (by Faradayís Law) under alternate magnetic fields and produce electrical currents that dissipate energy by Ohmís Law. 2. Magnetic losses refer to the energy dissipated when the alternate magnetic field acts on a ferro- or ferrimagnetic material, rotating its atomic magnetic moments and therefore making magnetic work on the material. The work per cycle is numerically identical to the area within the magnetic hysteresis loop in a B-H graph. Therefore when a magnetic material is subject to a time-varying external field H(t),† the mechanisms of energy dissipation taking place will depend on whether the material is metallic, magnetic, or both.

Below we will only describe the process of Magnetic Losses, i.e., ferromagnetic materials under ac magnetic Fields. For more on Eddy Current Losses, go here. |

|

This energy is converted into HEAT. |

|

The POWER dissipated in a cycle of B is just the work done per cycle times the frequency at which cycles are completed: |

|

When the material is insulating (no free electrons to go around) AND magnetic the same ac magnetic field generates displacements in the domain walls of the material. This process of creating, displace or extinguish a magnetic domain requires some energy. The energy is gained or lost in an irreversible way, and is an intrinsic behavior of a magnetic material. This irreversibility yields to the M vs. H curves known as hysteresis cycle. |

|

Core losses: Hysteresis and eddy currents are, for example, the origin of the temperature rise in electrical motors. These losses can produce as much or more heat than I2R losses. Design factors affecting those losses include lamination thickness, flux densities in the armature, and frequencies generated in the core that depend upon the number of poles and speed. Ambient temperature is the third most important factor determining motor temperature rise.

|

|

SUGGESTED READING ∑ David Jiles, Introduction to Magentism and Magnetic Materials Chapman and Hall (1991). ∑ D.H. Martin, Magnetism in Solids, 1llife, London (1967) ∑ S. Chikazumi, Physics of Magnetism, Wiley, New York (1964) ∑ B.D. Cullity, Introduction to Magnetic Materials, Addison- Wesley (1972) ∑ A.H. Morrish, Physical Principles of Magnetism, John Wiley, New York (1965). ∑ K. Moorjani and J.M.D. Coey (Eds.) Magnetic Glasses, Elsevier (1984). |

|

The frequency f: it is also clear from the left figure that the higher the frequency, the more times per second I will walk a complete cycle, and therefore the Power (energy rate) will increase. While in electrical applications we try to minimize there power losses (for maximizing the direct transformation from electrical to mechanical work), in MFH applications the goal is the exact opposite, i.e. to maximizing the amount of power loss (for heating purposes). |

|

Look what magnetic losses can do for inductive heating here (video) |

|

Magnetic materials materials are characterized by the existence of magnetic domains. Within a single domain, all atomic magnetic moments are parallel to a given crystallographic direction, called the easy axis of magnetization. In the absence of an external magnetic field, a piece of bulk ferromagnetic material is composed of randonmly orieted magnetic domains. A time-variable magnetic field in a metallic material induces electrical currents on its surface (parasitic or eddy currents). When the material is insulating (no free electrons to go around) AND magnetic the same ac magnetic field generates displacements in the domain walls of the material.

If the material is composed of few-nanometric particles, domains no longer are able to form and the external field will produce (depending on its strength) the coherent rotation of all magnetic moments in the material. For a multi domain material, the process of creating, displace or extinguish a magnetic domain requires some energy. This energy is gained or lost in an irreversible way, and is an intrinsic behavior of a magnetic material. This irreversibility yields to the M vs. H curves known as hysteresis cycle.

|